I’m currently studying an MA in Creative Writing at The Open University. This piece was my first attempt at ‘Place Writing’ and is the final version of my third assignment of Part One of the course.

You can’t get to Glastonbury without making an effort. The nearest station is 16 miles away. Go by road and the journey often feels interminable. But for Christians, Pagans, Mods, Rockers, Indie Kids and Trustafarians alike, this corner of Somerset is a special place.

I realise just how special as I listen to R.E.M conclude the first night of the 1999 Glastonbury Festival. One of the biggest bands in the world is playing to a huge crowd and I’m directly in front of the stage with the best possible view. I’d been to gigs before and even to a couple of smaller festivals. But this was something else; a level of joy I’d never experienced. I’m leaning on a metal fence, drenched in sweat and flanked by a couple of security guards, who are ready to lift me straight over that fence if I get crushed. There are thousands of people behind me, but virtually no-one in front. There’s one song to go. Four bars of rat-a-tat drum solo rush over our heads and the vocal starts:

“That’s great, it starts with an earthquake

Birds and snakes, and aeroplanes

Lenny Bruce is not afraid”

My first Glastonbury Festival started a couple of days before R.E.M. blew my mind. I travelled with a school friend and a couple of his mates and – perhaps unwisely – persisted with my plan despite being on crutches. An 18-month wait for a knee operation had ended 10 days earlier and against my Dad’s advice, I’d gone west with my leg in plaster and desperately hoping for dry weather. My campmates helped put up my tent and Jon – who I’d met for the first time that morning – wandered down to the markets, returned with an inflatable armchair and said:

‘Whenever you’re in camp, this is your chair’.

I’d learn that small acts of kindness and friendliness like that were common during my visits to Somerset. One such moment was the reason I was within touching distance of the band. As I made my way towards the Pyramid Stage, a security guard stopped me.

‘You’re a safety hazard on them, son. You’d better come with me.’ Talking into his radio and parting the crowd as we went, the security guard positioned me right against the crush barriers nearest the stage and introduced me to my minders. ‘Any problems, these lads’ll have you over the fence’ he said, smiling. ‘Have a good night.’

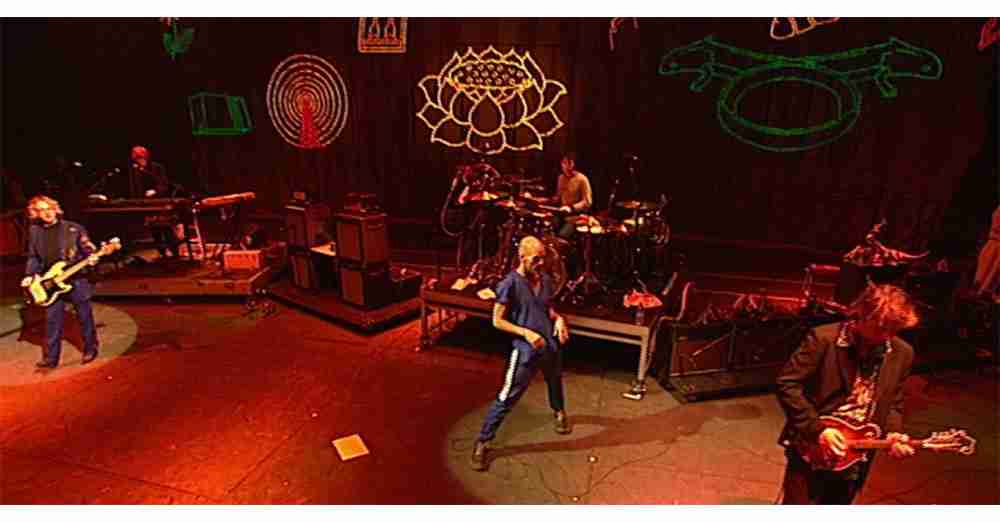

Moments later, just feet away and almost directly above me, Michael Stipe began singing and I was taken to another world. I knew who R.E.M. were, but only through their megahits. I had no idea that the band had formed in the year of my birth, or that they’d released eleven studio albums. Like me, they were at Glastonbury for the first time and I became a big fan that night. From the raucous energy of The One I Love and the perfect pop of Losing My Religion, then throughout their set, the trio from Georgia were phenomenal. To this day, if I close my eyes, I see the neon lights which cascaded across the stage backdrop, feel the songs pulse through my body.

That night was and remains a genuinely spiritual experience for me. After the Festival, I became as desperate for live music as any addict becomes for their next hit. Work was the means to an end – the end being the next gig I could get to. Within a year, there was barely a live music venue in London I hadn’t visited at least once. Some became firm favourites and semi-regular haunts. None has ever had the allure of Glastonbury.

***

Between 1999 and 2010, I went to six Glastonbury Festivals. Over this period, the scale of the Festival exploded and no two visits were the same. My first and last were both sun-baked, dry and hot weeks, but 2005 was nearly a disaster. Our group arrived on Wednesday lunchtime and the plan was to camp on Pennard Hill, as in previous years. We turned up during a heatwave and the knee which had left me on crutches a few years earlier was troubling me. When we reached a spot where we’d camped before, I refused to take another step.

‘We camped here last year. This is a great spot!’ I said, hurling my rucksack down.

‘We should go a bit further up the hill’ said my friend, Ian, who’d been studying site maps for weeks.

‘Fuck that! It’s about a hundred degrees, we’ve been hiking for ages and my knee is fucking killing me. I’m not going any further.’

My stroppiness would prove prescient. In the early hours of Friday morning, a biblical storm broke over Worthy Farm. I remember the rain waking me up. I poked my head out of the tent and swore at the ferocity of the downpour. By breakfast time, two months’ worth of rain had fallen onto parched ground. As the water zigzagged down Pennard Hill, it took the top layers of earth with it, causing an enormous mudslide.

Our camp was spared by a few metres but many weren’t so lucky. When we eventually squelched around the site, we saw the devastation wrought by the weather. Countless tents were almost entirely submerged by the mud; some had been swept away completely, including those which had been pitched where Ian had wanted to camp. The main tent in the Dance Village had been struck by lightning. The show went on, eventually and I dodged the cold by wearing a weatherproof suit usually provided by my football club to the substitute players.

Two years later, the rain was constant and the mud deep but worst of all, the weather wrecked the acoustics. The 2007 Saturday night headline set, performed by The Killers, was almost inaudible, even though my friend Teri and I were pretty close to the stage. Not R.E.M close, but we should have been able to hear the band. We began to chant ‘Turn it up! Turn it up!’ between songs and before we knew it, thousands of people had taken up the call.

Conditions were grim all week, but even when the weather was bleak, there was a beauty and energy about the Festival site I’ve never found anywhere else. Despite the temporary nature of the set-up, it feels permanent. Once you’ve been a couple of times, it has a familiarity but, because the Festival has expanded over the decades, there were always new areas to explore, meaning that while the returning attendee feels “at home”, the sense of wonder generated on the first visit never completely leaves you.

***

My most powerful memories of Glastonbury are those which involve my wife, Stephanie. We met in 2007 and our relationship began some months after I’d returned from Pilton with a tobacco-coloured T-shirt and a mild case of Trench Foot. I thought that 2007 might be my last Festival, but Steph bought me a four-person tent for my birthday and we picked up tickets soon after that.

I didn’t know until the 2008 trip that Glastonbury is considered the “cradle of British Christianity”, although I’d read that it had a long association with Paganism which not only continues today, but has influenced the local landscape. Whether at the Festival or in town, it’s impossible not to notice Glastonbury Tor, which completely dominates the skyline. The Tor is a spectacular hill and considered one of the most spiritual sites in the country. There is a sort of terracing around the Tor which has been interpreted as a maze based on an ancient mystical pattern. The maze was probably created four or five thousand years ago, around the same time as Stonehenge. It’s said that beneath the hill there’s a hidden cave through which you can pass into the home of Gwyn ab Nudd, lord of the Celtic underworld. Glastonbury Tor is also reputed to be the burial site of the Holy Grail, which was apparently brought to Britain by Jesus’s uncle, Joseph of Arimathea. Given that the Celts and the Christians both consider Glastonbury Tor important, is it surprising that Festival visitors feel something in the air when they arrive?

Steph once told me that arriving in Glastonbury ‘felt like leaving the UK and arriving in a different country’. I knew what she meant; I could definitely feel an energy in the atmosphere that hadn’t been present at home. We’d arrived on the Tuesday of Festival week, having pre-booked a Bed and Breakfast. Glastonbury High Street certainly doesn’t look like the identikit town centres you can find up and down the land. You won’t find Marks & Spencer or McDonald’s there. Instead, you can shop at The Crystal Man, The Wonky Broomstick, or at any of the town’s three independent bookshops. On that Tuesday afternoon, I bought a beautiful but impractical pair of tangerine wellies at a spectacular shop called Look At My Funky Shoes. They were far too tight and Steph had to prise me out of them and buy replacements from a tiny branch of Millets on the Festival site. She still laughs at me for buying those bloody boots (but these days, I join in).

The 2008 trip wasn’t just marked by my first experience of Glastonbury’s unique town centre. Steph had her own spiritual experience of live music. Even now, she speaks with the same awe about Florence and the Machine’s performance in a bar next to the Other Stage as I have about R.E.M.’s 1999 show. With good reason; it was a wild, spectacular performance. Florence Welch possesses a remarkable voice but on that Saturday teatime in the Queen’s Head, she added a boundless energy, climbing the speaker stacks and, at one point, shimmying up one of the poles holding the tent up before hanging off it to sing. It was during that show that Steph understood why I was so passionate about live music. The year before, I’d seen Florence and the Machine’s first-ever Glastonbury set, in the Tiny Tea Tent in the Green Fields, along with about 30 others.

Believe it or not, I have taken to the stage at Worthy Farm. Having wandered into one of the Cabaret areas after the main stages had shut down one night while slightly inebriated, I ended up being goaded into an audience participation segment in what I think was a magic show. The exact details of what happened escape me, but I know that my part in the performance ended with a bucket of water being dropped over me. I was a bit slow to react to the soaking, and the performer who coaxed me onto the stage told me I could return to my seat by asking ‘what more do you want? A biscuit?’

No, ideally, what I want is to go to the 2023 Glastonbury Festival. But the trip Steph and I made to the 2010 event felt like the end of an era, for all kinds of reasons. Parenthood represented the biggest shift. We missed the 2009 Festival because Steph was pregnant with our first child, but had bought tickets for 2010 because my Mum had offered to have Lilly while we were away. Mum passed away suddenly between the ticket sale and the Festival and my in-laws stepped in so we could still go. Perhaps we shouldn’t have.

‘Gareth, I’m about to pass out.’

Steph looked terrible. After five days of oppressive heat, she was flagging badly. It didn’t help that shade seemed to be harder to find than ever, or that we were both preoccupied. I was trying to process losing my mother; Steph was fretting about the 11-month-old daughter we’d left back in London. Lilly spoke for the first time that week, but we weren’t there to hear it.

It was as if real life had invaded the self-contained world the site became on Festival week and we struggled to find the joy that had filled previous visits. Steph’s case of heatstroke felt like just another difficult moment in a difficult week but was about to take us to a surreal place. We were walking through the Dance Village when Steph became ill and I asked the closest member of festival staff for help. It turned out that to get Steph some help we had to go backstage.

Getting backstage at Glastonbury is the kind of experience most music fans would dream of. We found ourselves in a tall red tent which didn’t even have a groundsheet, although it did have ice-cold water and several well-meaning blokes bearing fans.

‘I’m sorry, I’ve ruined it!’ Steph wailed.

‘Are you joking? I’m grateful for the shade. Plus, look at the positives; we’re backstage at Glastonbury!’ I replied, trying to reassure my girlfriend.

During the 2010 trip, we also spent time up at the Stone Circle. This is a megalithic monument of standing stones which looks ancient, but was built in 1992. You get there by going through the Green Fields. From here, you can see the whole Festival site and Steph and I both loved just sitting up there and catching our breath. Once you’re up there, everything changes. This is a place to reflect, to calm down. Many Festival-goers consider this part of the site to be a sacred space and I vividly remember one spectacular sunset, where I looked up at the sky and thought about not just Mum, whose death was still so raw and felt so unfair, but Dad, who had died in 2007 and whose passion for music had inspired my own. I thought about Lilly and the joy she was bringing to our lives. I looked across at Steph, who had been so supportive since Mum’s passing. We sat in silence, watching the blues, pinks and oranges dancing across the horizon. For the first time in months, I felt at peace.

During the last night of the 2010 Festival, as I watched The Levellers on some obscure stage, I felt old for the first time. This was a different Glastonbury to the one I’d discovered; much larger, brasher, louder. Thanks to annual coverage on the BBC, Glastonbury was becoming a rite of passage for bands and festival-goers alike. No longer solely for hippies and New Age Travellers, Glastonbury was turning into the world’s biggest, most famous music festival. I was thirty and had a baby at home; this wasn’t my week anymore.

I have returned to the town of Glastonbury a couple of times since 2010. Some things have changed; you can’t Look At My Funky Shoes any more, because the shop’s closed down. The tangerine wellies ended up as planters in which my mother-in-law grew flowers. Yet, Glastonbury still feels like a town apart from the world. One day, I hope that we can take our children to Glastonbury. It doesn’t really matter if they go to the Festival. All that will matter is that we get to experience the magic of the place, as a family.